Communities across Canada are set to mark the country’s first National Day for Truth and Reconciliation today, honouring Indigenous survivors and children who disappeared from the residential school system.

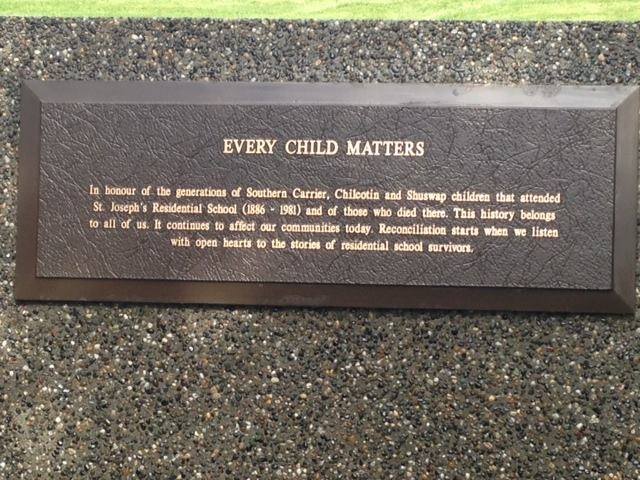

Singing and drumming were scheduled to ring out at 2:15 p.m. from Kamloops where the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc Nation announced in May that ground-penetrating radar had detected what are believed to be 215 unmarked graves at the site of one of the largest former residential schools.

Numerous Indigenous nations have since reported finding unmarked graves at former residential school sites with the same technology used in Kamloops, prompting calls for justice that have resonated across the world.

The federal government announced the new statutory holiday in June to commemorate the history and ongoing impacts of the church-run institutions where Indigenous children were torn from their families and abused.

The last residential school in Canada closed in 1996.

Generations of Indigenous children attended the institutions and the trauma from them has been passed down, Teegee said in an interview, pointing to the ’60s Scoop — when Canadian governments placed thousands of Indigenous youth in foster care — and to the disproportionate number of Indigenous youth in care today.

There’s a risk the meaning of reconciliation could become “watered down” without substantive action and funding from the Canadian government to address the mental health challenges, addictions, homelessness, discrimination in the health-care system and other social harms related to residential schools, he said.

Teegee said gestures, such as acknowledgments of Indigenous lands, lowering flags to half-mast to honour residential school victims and an apology from the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops, are needed, but gestures only go so far.

“That doesn’t change tomorrow for an Indigenous person who’s dealing with addictions or dealing with mental health issues because of residential schools.”

A number of extensive reports — from the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples in 1996 to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and to the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls — have made recommendations to address the discrimination and harms Indigenous people face, Teegee said.

“We’re one of the most studied groups out there,” he said. “Yet we’re still dealing with the same old issues over and over again.”

“We’re tired of being studied.”

The federal government has pledged to implement the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s calls to action and the B.C. government is in the process of aligning its laws with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. But Teegee said he would like to see more concerted plans, timelines and funding.

Ultimately, Teegee said he sees reconciliation as changing the relationships between Indigenous nations and Canadian governments to recognize Indigenous Peoples’ sovereignty and self-determination over their territories and affairs.

“This is a long-term commitment between Indigenous Peoples and regardless of what party you’re in or the colonial state, regardless of what affiliation you have.”

It’s about creating space “to be First Nations, to be Indigenous, and to be in a place that respects our identity and respects who we are,” Teegee added.