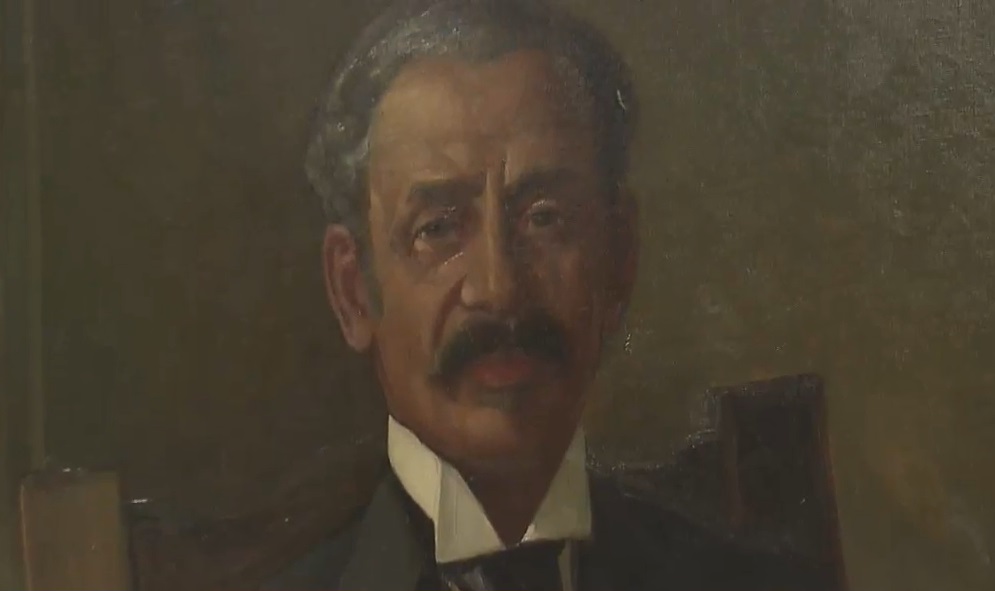

His portrait hangs in Toronto City Hall and in 2016 an east-end park was named after him, but during his time in office after becoming the first Black person ever elected to Toronto city council in 1894, William Peyton Hubbard faced the cruel indignities of rampant racism.

In Toronto, where Hubbard would go on to eventually serve as acting mayor, Blacks were barred from many restaurants, theatres and hotels and when travelling to Washington on business, Hubbard had to carry a letter from Mayor Emerson Coatsworth, vouching for his good character.

Less than a decade before the slave trade would be abolished in the United States in 1865, one prominent Canadian politician publicly referred to Blacks as “necessary evils, only submitted to because white servants are so scare.”

Those hateful words were penned by Colonel John Prince, who was then a leading member of Ontario’s Legislative Council.

Published in the ‘The Toronto Times’ in 1857, Prince went on to write that Blacks were, “the greatest curse ever inflicted upon the magnificent counties which I have the honour to represent in the Legislative Council of this province.”

It is from that bigoted backdrop that Hubbard, the child of slaves from Virginia who escaped on the Underground Railroad, rose to prominence in public life.

Humble beginnings

“He had very humble beginnings, he started his career as a baker,” Nikki Clarke of the Ontario Black History Association, told CityNews after local residents voted to name a park near Broadview Avenue and Gerrard Street East after Hubbard.

If you look at the year (when he was first elected) 1894, and the abolition of slavery was roughly around 1864-65, it’s not a huge span of years. So, from slavery to city alderman is a huge leap.”

Historian and political writer Mark Maloney told CityNews in a past interview that Hubbard was one of the fathers of Toronto Hydro.

“In those days the electricity service was all in private hands amongst different companies. And he and a number of other people rallied about to say we should have a public hydro owned and operated by the citizens.”

“Hubbard went into politics in the 1890s, he lost his first election but then he won in 1894,” Maloney explained. “He was a reformer, he went after corruption and he wanted improvements to the Waterfront and Toronto Island and the Works Department. He was quite a fighter in his day.”

“There was a lot of prejudice as he was growing up, the Civil War was on in the U.S.”

Hubbard became revered for his honest reputation, and he wasn’t afraid to expose injustice and stick up for those he felt were being discriminated against, including waging a fight to end unfair taxes against Toronto’s Chinese community and defending Jewish people against anti-Semitic attacks.

His competence and credentials led him to a powerful elected position on the four-man Board of Control.

“In 1904, Toronto brought in a new structure which lasted until 1969 and it was called the Board of Control…you had four controllers elected city-wide…that was your executive committee for the city, so all your major decisions had to first go through the Board of Control which was chaired by the mayor,” Maloney explained.

Lasting legacy

In 1987 the City of Toronto established the William Peyton Hubbard Award for Race Relations.

The city’s website says “the award is presented to a Toronto resident or non-profit organization whose outstanding achievement and commitment has made a significant contribution to challenge racism and support a more harmonious city.”

Honouring his “unwavering commitment” Hydro One sponsors two annual awards in Hubbard’s name for outstanding Black undergraduate students attending an Ontario college or university, doling out cash rewards and paid work term/ summer positions with Hydro One.

During the ceremony unveiling Hubbard Park back in 2016, Toronto’s only Black councillor, Michael Thompson, said of Hubbard, “I’m standing on the shoulders of greatness.”

“We need to ensure his vision is not forgotten. The citizens of Toronto benefited from his greatness.”

Hubbard died in 1935, but not before his own words in a letter to a friend echoed a sentiment that is still felt today by racialized people struggling in the face of enduring systemic racism.

“I have always felt that I am a representative of a race hitherto despised, but if given a fair opportunity would be able to command esteem.

Citynews Toronto